New Strategies for Climate and Security

Geneva, 6 October 2021

The Workshop on New Strategies for Climate and Security held in Geneva on 6 October 2021 was organised by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs in cooperation with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) and the Environment & Development Resource Centre (EDRC). The multidisciplinary event brought together 38 expert analysts and practitioners from international and intergovernmental organisations, think tanks and NGOs with offices in Geneva.

The meeting was held at the at the Maison de la Paix.(Photo by Hennings.iheid)

In his welcome message, Ambassador Thomas Greminger, Director, Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) said that “the latest IPCC report is only the most recent testimony to the fact that security professionals need to factor-in climate change repercussions on security”. He stated that “With this workshop we have the opportunity to strengthen the role, outreach and ultimately impact of international Geneva on peace, human security and sustainable development, on a national and global scale. Indeed, I think that Geneva with all its organizations and NGOs in the different thematic clusters is very well placed to discuss such a cross-sectoral issue like climate change and security.”

How to motivate concrete collective action? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 Crisis

In his presentation, Alexander Verbeek, Policy Director, Environment & Development Resource Centre, explained that the current pandemic and climate crises are different in nature:

• Covid-19 is health-related rather than environmental.

• Covid-19 is potentially acute and relatively short-term, while climate change is chronic and long-term.

But, both crises also have a lot in common:

• They overlap, both are global (but also national and local), deadly, world changing (although we don’t know yet how). Both have also been predicted by scientists.

• Both crises can only be solved by international cooperation. Or to stay with the title of today: both require collective action

• Both grow exponential, and that means that urgent action is required.

• But the sense of urgency is not felt the same by our government leaders.

Mr Verbeek added that “If historians in 100 years from now will look back at these crises, then they will be most fascinated by the inability of our governments to come with an adequate response to the climate crisis”.

“I think”, he said, “these future historians will be less critical on the response to the pandemic. At least here in Europe we haven’t done so bad. In a relatively short time we really changed all of society to fight the pandemic.”

But, if historians in 100 years from now will look back at these crises, then they will find it hard to understand why

• On the one hand the leaders in Europe did listen to scientists, and followed their advice on the pandemic,

• But why on the other hand these same politicians ignored the science of climate change for so long.

So why is there this difference in approach between the pandemic and climate change?

Mr Verbeek said he saw three elements that may have played a role.

First, the connection between getting infected by the virus and dying is much easier understood than the long-term impact of climate change. Your next holiday flight to Spain contributes to the drowning of an island on the other side of the planet.

Second, the pandemic is a huge catastrophe, but we know that we can get it under control and that the basic structure of society and international relations will not be dramatically changed.

Climate change is not like that. It could have been like that if politicians worldwide would have taken measures that scientists advised thirty years ago. But now that is no longer the case. Wars end, pandemics end, but global warming has now become so bad that we have passed tipping points. Some of the destruction of our planet that we have created will only be repaired on a geological time scale that is irrelevant for humans. And some will never return. You won’t get some of the Antarctic ice shelves back in place and there won’t be Northern White Rhino’s in ten years or in a million years.

The third reason why the response is so different is because of the parties that will be impacted by the crisis, and by the measures taken, will be different.

Except for a few big enterprises, nobody gains from the pandemic, or loses when we beat the virus. But for tackling climate change, some of the most rich and powerful people in the world will have to do a step back.

- Any equality gained from fighting the source of the pandemic, like giving vaccines to the people in the global south, serves a self-interest.

- But, If you want to help those in the global south by stopping the production, and use of fossil fuels, that will help.

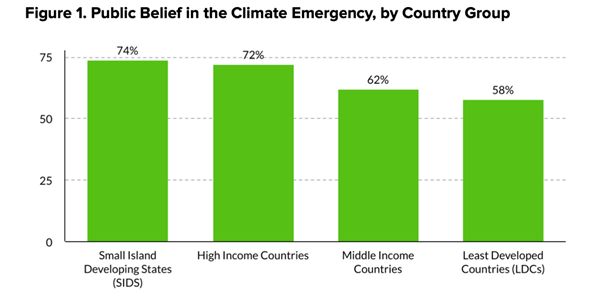

Concerning the public concern about climate change, Mr Verbeek reported that last year, UNDP carried out the largest-ever survey of public opinion on climate change. It found that 64 percent of people in over 50 countries surveyed around the globe recognised climate change as a global emergency that must take priority.

The survey was conducted during the COVID-19 crisis, but still the people in the world want their leaders to prioritise the climate crisis. So our leaders have the mandate to act decisively.

In speaking on the solutions, Mr Verbeek said that the main lessons learned are that good governance matters, science matters, and trust in governance and science is essential. He added that “a lesson that I fear we will draw more clearly in one or two years from now is that tackling inequality is relevant for all. New mutations of the virus will develop if we don’t vaccinate the people in the poorer countries.

The same is true for climate change. Even if you ignore the moral aspects of why we should help other, poorer, people, we will see that the problems caused by climate change will not stay in the poorer countries that hardly contributed to the problem but that are worst hit”.

What do the latest climate models tell us about the key risks to the planet post 2030?

Sonia Seneviratne, Professor for Land-Climate Dynamics at ETH Zurich and coordinating lead author of the 6th assessment report of the IPCC provided in-depth information on “What do the latest climate models tell us about the key risks to the planet post 2030?” Her presentation was based on the Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis released on 9 August 2021.

The presentation began with information on the observed global warming in which the warming rate is unprecedented in more than 2,000 years and the temperature level is unprecedented in more than 100,000 years. She added that the largest part of this warming is irreversible for several generations. The IPCC AR6 reports states that “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land”.

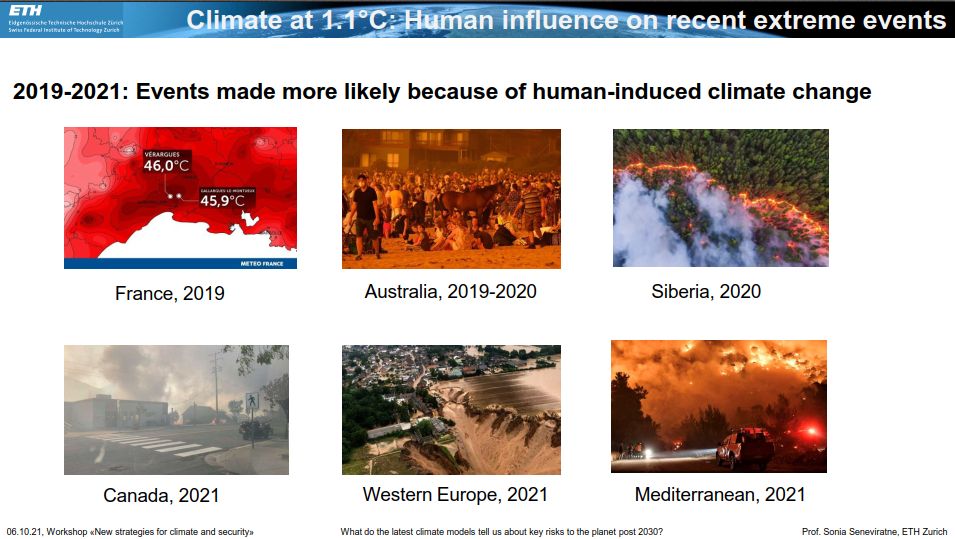

One slide showed several recent events made more likely because of human-induced climate change:

About projected changes in extremes as function of global warming the Prof Seneviratne reported that many changes in the frequency and intensity of climate extremes become larger with increasing global warming:

• hot extremes

• marine heatwaves

• heavy precipitation

• agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions

• proportion of intense tropical cyclones

With further global warming, every region is projected to increasingly experience multiple changes in climatic impact-drivers, including extremes

• Many regions are projected to experience an increase in the probability of compound events with higher global warming (high confidence):

• Concurrent heatwaves and droughts are likely to become more frequent

• Further increases of fires and compound flooding (high confidence)

• Concurrent extremes at multiple locations become more frequent, including in crop-producing areas, at 2°C and above compared to 1.5°C global warming (high confidence)

Concluding that unprecedented events become more likely with increasing global warming and d that threats from extremes are multiplying with increasing global warming, Prof Seneviratne concluded that "We should do all we can to limit global warming to ~1.5°C and avoid overshoots: Even a world at ~1.5°C is not safe, but it’s the best option we have.”

Addressing climate-related security risks on the ground: Early warning and integrated programming solutions

The presentation by Silja Halle, Programme Manager, EU-UNEP Climate Change and Security Partnership, UNEP Environmental Security Unit, entitled “Addressing climate-related security risks on the ground: Early warning and integrated programming solutions” covered three main areas. In Part 1 on the Policy and Operation Context she explained the challenges to the implementation of UNSC mandates including limited climate and security analysis capacity, lack of data and analysis platforms and lack of evidence base on solutions and how each of these are being and can be addressed.

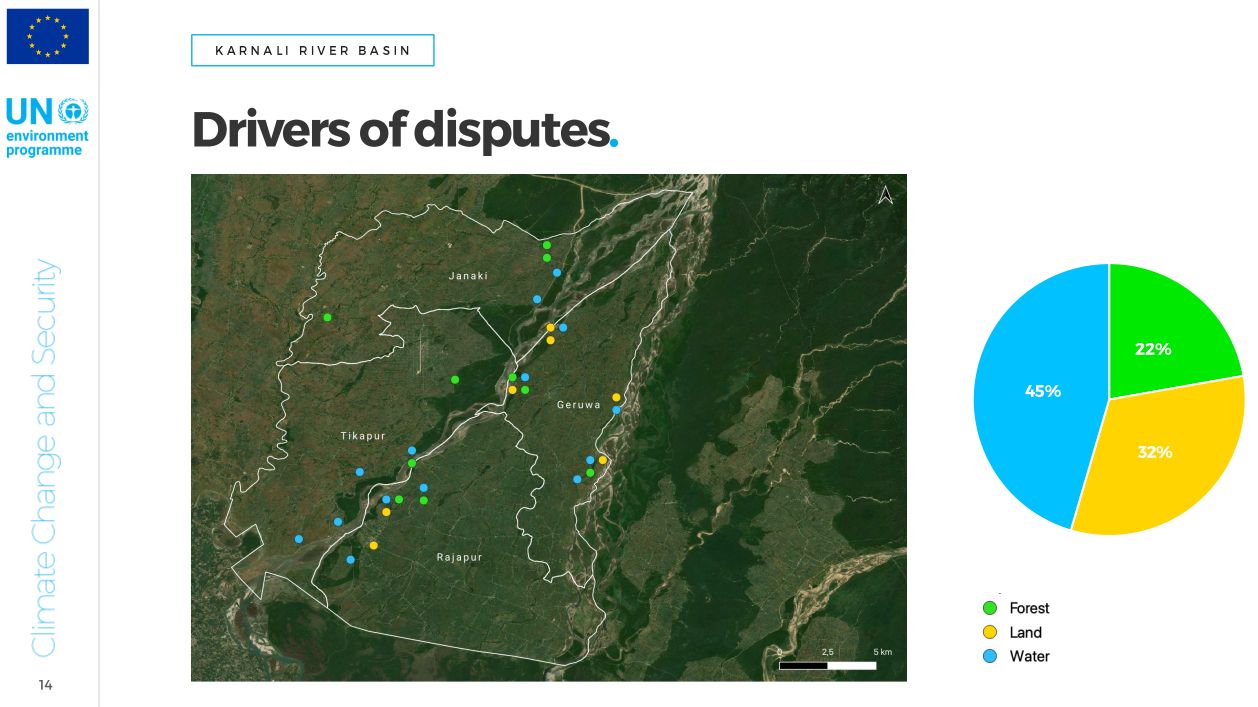

Part 2 on Project Results and Lessons Learned focused on pilot projects in Sudan and Nepal in which the three core results were a) Strengthened capacity of communities to mediate disputes and prevent natural resource-related conflict, b) Enhanced social cohesion and trust, and c) Sustainable and climate resilient livelihood options for vulnerable groups.

The lessons learned from these successful projects included:

1. Climate adaptation and resilience building interventions can contribute to peacebuilding at local levels, when delivered in a conflict-sensitive manner. That requires contextualized integrated analysis and inclusive processes;

2. In conflict-affected and climate-vulnerable contexts climate change adaptation interventions offer opportunities for strengthening the leadership, political and economic inclusion of vulnerable or marginalized groups; and

3. Influencing national planning and policy practices on climate-related security risks requires sustained technical engagement with government stakeholders.

In the case of Karnali River Basin in Nepal the EU-UNEP project has shown the percentages of disputes driven by issues related to forests, land, and water:

Part 3 on Building Capacity on Climate Security focused on practical initiatives to strengthen capacity to identify, assess and act on climate-related security risks. Several reports, toolboxes and guidelines were highlighted including those directed toward Political analysts and peacebuilding practitioners, climate adaptation specialists, and Gender and inclusion advisors.

Session 2: The Response of Geneva-based Organisations to Climate Change Security Risks

For this session, the audience was split into three parallel Working Groups, which each discussed the following two topics. (See the annexed programme for the more specific questions within these topics).

A. How is your organisation dealing with Climate Change Security Risks today?

B. How can readiness within and among your organisations be increased?

Each group included representatives from the various tracks (Humanitarian and Development operations; Mediation, Peace and Security; Environment and Climate). Participants benefited from learning more about their respective activities related to climate change and human security and assessed together what is needed to increase the effectiveness of their work.

Session 3: The Role of Geneva: New Strategies for Climate and Security beyond 2030

In this session moderated by Anna Brach, Senior Programme Officer, Head of Human Security, GCSP, and Ronald A. Kingham, Executive Director, Environment & Development Resource Centre (EDRC), there was a participatory discussion on Integrating Development, Humanitarian Action, Climate Change, Peace and Security. The lead questions focused on the role of Geneva, how collective and coordinated action could be incentivized and on how concrete ideas could be implemented to address climate and security risks. More than 40 specific observations and ideas were put forward. These included:

• The real added value of Geneva based organisations lies in focusing on the impacts of the climate crisis on people. Further, Geneva can bring the knowledge of the humanitarian approach and its experiences on the ground into the global conversation around solutions to the climate crisis.

• There is a need to achieve real transformative recognition of the human security implications of climate change. This means involving different actors and specifically addressing problems of the nexus between climate change and security.

Session 4: Conclusions and Follow-up; Closing of the Workshop

In the closing session, the moderators stressed that Geneva really has a unique perspective especially because of the wealth of organisations found on site. Against the background of the increasing problem of the climate crisis, Geneva-based organisations have a lot to offer, both in terms of conceptual approaches as well as in terms of concrete action. Good coordination among relevant Geneva-based organisations is something that is necessary, and it is important to avoid overlap with other existing initiatives.

Principles articulated during the workshop included the need to understand human security not only in the terms of protection but also in the context of empowerment. It is also important to address the disconnect between the local level and the higher political levels of governance. Through this workshop it was made very clear how through working together Geneva-based Organizations can connect the stories from the field and bring them to the attention of decision makers and of the private sector.

The workshop demonstrated the importance of identifying, designing, and implementing response mechanisms to prevent conflict and foster sustainable peace and security. Geneva has the strength, experience and knowledge to make an important contribution in looking at climate change and human security in a very concrete and comprehensive way.

Cover photo from “Closing the gap on climate action” Zurich Insurance Group 2021